In chapter 10 of

Cutting Edge, entitled “Structural

Unemployment and the Qualitative Transformation of Capitalism”, Thomas Hirschl

examines Marx’s theory of capitalist development, specifically focusing on the

possibility for and effects of a social revolution in capitalist society. According to Marx, “[A]n era of social

revolution begins when the technological capacity of society supersedes or

becomes too productive for the existing property relations” (Davis, 158). The explicit connection that Marx draws

between social revolution and technological advancements is addressed by

Hirschl, who seeks to argue that, “[G]iven the framework of Marx’s dynamic

theory of capitalist accumulation, the introduction of electronic technology

is, indeed, a catalyst for revolutionary change” (158). Indeed, Hirschl is a proponent of what he

suggests is an imminent social revolution.

What this revolution might mean to capitalist society itself is a topic that

he addresses throughout the chapter.

I found

Hirschl’s ideas to be in significant conversation with Guglielmo Carchedi’s

examination of advanced technologies and the productivity of labor, which we looked

at last week in chapter 5. In his

chapter on the promises and realities of technology in the twenty-first

century, Carchedi examines the effect/s of technological advancements on the

labor force, ultimately cautioning that the cyclical process of technology

replacing labor will result primarily in unemployment, poverty, human

exploitation, starvation and despair. His

fear is not unfounded, nor is it particularly new, as this clip from The Twilight Zone (1964) illustrates:

Here, a single

supervisor (Hanley) is replaced by a machine that is purportedly more precise

and effective than he is. Initially Mr. Whipple

(the boss) is pleased with his purchase, despite the fact that it earns him his

employees’ scorn and leads to him being punched in the face. As the episode progresses, however, Mr.

Whipple becomes increasingly obsessed with the machines in the factory, and is ultimately

replaced by one himself, lamenting “It

isn't fair, Hanley! It isn't fair the way they [machines] ...diminish us”

at the end of the episode. Although this

episode of The Twilight Zone is

nearly 50 years old, I found it extremely interesting that even then, the

sentiment that “no one is safe from technological advancements in the work

force, not even the boss” still rang oh-so true. It is this sentiment that underscores

Hirschl’s imperative that,

“As more and more firms in

the economy adopt these [ever-advancing] technologies, the total amount of

productive labor in the system declines, and the rate of profit falls. This increases unemployment, heightens

realization crisis, and thereby sets the competitive conditions encouraging another

round of technological adoption. This

cyclical process defines the ‘final’ decline of capitalism” (164). Here, Hirschl not only echoes Carchedi’s

theory of the impact of technology on productive labor, but uses it to

underscore, and even announce Marx’s theory of social revolution and the

decline of capitalism.

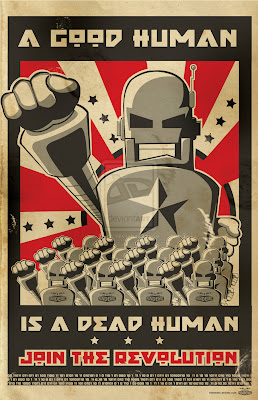

One

of the more interesting things I came across while looking for a contemporary

application of Marx/Hirschl's theories was an entire collection of

propaganda-esque art signaling the beginnings of a robot revolution (or

robolution). This image signals our demise at the hands of our own

creations, an anxiety that is echoed throughout a litany of science fiction writing. Does the end of capitalism signal the end of

man? I’m inclined to say of course not, but a small part of me

can’t help but wonder. If we are moving

towards wageless production, my guess is that the road ahead is long, windy,

and covered in blood (and circuitry).

I like the clip. And you raise good points. I share your dissatisfaction with signals of the demise of capitalism through automation (or "roborevolution"). Here's why: it seems to me that such a demise might easily bring about feudalism, or some sort of fascism, political-economic arrangements in which the worker is not only exploited, but suppressed and even tortured. I'd much rather live in a capitalist arrangement than a fascist one. It seems to me that a good, worthwhile social revolution will enact an arrangement that is better than capitalism at minimizing suffering for masses of people. I'm not sure what such an arrangement would look like, and I'm doubtful that the demise of capitalism, if it ultimately happens in the near future, will lead to such an arrangement.

ReplyDelete