Some Issues with High-Tech Hype

Before examining the totalizing effects of a labor/workforce overrun by electronic technology, it is significant to note the preliminary and incremental changes that occur when a new technological innovation is introduced into the workforce, particularly when it impacts productivity. Elements of these changes are present in “Obsoletely Fabulous,” which begins with Bender, Fry, Leela and Professor Farnsworth (the show’s main protagonists) visiting a “Roboexpo” that showcases new and improved robots available for purchase. It is important to note that Futurama itself takes place in a futuristic setting (roughly the year 3000) in which robots are common fixtures both as tools for human comforts (essentially highly technologically advanced appliances), as well as for companionship. Many robots in the show including Bender, whom “Obsoletely Fabulous” is centered around, are presented as autonomous, human-like beings that experience emotions such as jealousy, anger, sadness, love and a sense of self-worth. These dimensions of Bender and other robots’ personalities are intriguing when examined in parallel with their status as “objects” to be acquired by and for human consumption.

Given these parallels, the opening scene of “Obsoletely Fabulous” is particularly interesting, as it establishes that capitalism is still very much alive in the futuristic setting of the show, and calls into question what the impact of technological innovations will be on the robot labor force. This question becomes a real concern for Bender at the Roboexpo when Robot 1X, “A robot that will put all previous robots to shame,” (Futurama 2004) is revealed and overtly marketed as superior to its (now technologically inferior) predecessors.

As Guglielmo Carchedi points out, “Labor is continuously first expelled and then attracted in the different phases of the economic cycle” (Davis et. al. 80). In the scene pictured above, we can see Bender being expelled as a source of labor while Robot 1X is simultaneously attracted as the “new and improved” labor model. Significantly, Carchedi argues that, “The question of who the agents of social change will be if technology fully replaces labor is misplaced, given that labor cannot under capitalism be dispensed with” (80). I will return to the dimensions and implication of human labor in Futurama later on in this paper, but for now it is meaningful to establish capitalism’s role in the show.

Bender: That new robot is great huh? He sure made me look like a pile of crap.

Professor Farnsworth: Indeed! That why I bought one to help around the office.

Bender: [Gulp]

Because Bender occupies the unique role of being both a consumable product and a source of labor, he experiences a sort of double displacement, as he feels both competitive with and inferior to Robot 1X. Eventually, Bender falls into a deep depression because he feels that he cannot keep up with his new robotic counterpart.

The feelings

that Bender experiences at the hands of Robot 1X are not common, as Carchedi

argues, “While new technologies do raise human productivity in novel ways,

their capitalist use necessarily implies crisis, exploitation, poverty,

unemployment, the destruction of natural environments and more generally all

those evils which high tech is supposed to eradicate” (Carchedi, 73). While robot exploitation, poverty, and

unemployment are the implicit aftereffects of Robot 1X’s introduction into the

labor force, we as viewers see Bender explicitly undergo a state of personal

crisis, in which he feels inferior to Robot 1X and fears they will never “be

compatible.” To surmount this “fear”

Leela suggests that Bender visit his manufacturer for a “software update” that

will make him compatible with the new technology.

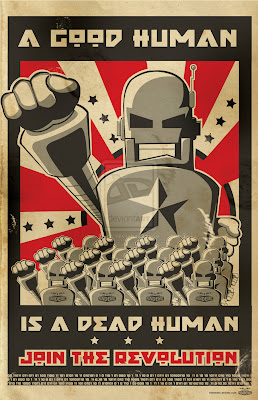

Structural Unemployment and the [Obsolete]

Robolution

Determined to co-exist with Robot 1X, Bender visits the robot manufacturing plant for his “software upgrade” but loses his nerve after watching another robot receive the upgrade and remarking, “It’s like he’s not him anymore— you took away his robo-humanity!” (2004). Fearing that he too will become brainwashed after receiving the upgrade, Bender flees from the factory and sits dejected in an empty alley lamenting, “I’m too scared to get the upgrade, but I can’t face my friends without it” (2004). Convinced that his utility to society has essentially vanished, Bender runs away from home in search of a place where he can live in inferior peace. Given the futuristic world that show is set in, viewers are positioned to view the adoption of major technological advancements like Robot 1X into society as the norm. This rampant adoption has the potential to be problematic for robots, as Hirschl argues, “Adopting these technologies… [I]ncreases unemployment, heightens realization crisis, and thereby sets the competitive conditions encouraging another round of technological adoption. This cyclical process defines the ‘final’ decline of capitalism” (164). Indeed, evidence of these “rounds” of technological adoption (and inevitable abandonment) emerges when Bender lands on a desert island occupied by obsolete robots.

After realizing

that the robots in the colony have gone through essentially the same form of

technological devaluation as himself, Bender begins to disavow technology and

its usefulness as a whole. Although they

are a small group, the obsolete robots living on the island come to represent

the structurally unemployed (individuals whose lack of employment results from

a mismatch between demand in the labor market and the skills and locations of

the workers seeking employment), and further come to constitute, “[A] ‘new

class’ that has nothing in common with either the capitalists or the industrial

working class. Their immediate class

interests are to transform the social system to distribute goods and services

on the basis of human need” (169).

Indeed, the robots on the island find themselves at odds with both

capitalists and the working class, and vow to bring forth the social revolution

that Marx foreshadowed as the final crisis in his theory of capitalist

development, only rather than distributing goods and services on the basis of

human need, their goal is to dispense of technology altogether.

Plans are set

into motion, and the robots make their way back to Manhattan in a primitive

submarine with the hopes of destroying Robot 1X. Their plans, however, are pathetically

thwarted, as their crude and imprecise tools not only fail to destroy Robot 1X,

but also cause a fire which traps all of Bender’s friends. In his attempt to abandon technology, Bender

trades his full metal body for one made of wood, and is therefore unable to

help rescue his friends from the fire.

As result, he must rely on Robot 1X to save them.

As Bender lies helplessly and watches the fire inch closer to his friends he wails, “Why didn’t I get that upgrade? I’m an outdated piece of junk!” Until he notices Robot 1X in the corner and exclaims, “Wait.. I can use you as a tool to save my friends, and I’ll still be the hero who everyone says how great he was.” True to form, Robot 1X swoops in and uses giant motorized fans to extinguish the fire, even managing to save what’s left of Bender along with his friends.

Information Capitalism, Upgrading, and the Future

After narrowly escaping

death thanks to the help of Robot 1X, Bender opts to get the software upgrade

in order for them to be compatible with one another. As he steps onto the machine’s platform,

Bender comments, “This new technology is great!

I love those 1X Robots, those guys are my beeest friends!” before it is

revealed to the audience that the entire “obsolete robolution” (and hence the

majority of the episode) was a hallucination brought on by the upgrade

software. It appears, then, that the

jobs of information capitalism are reserved for those who can perpetuate its

capitalist interests throughout society.

This is the chief enterprise of the capitalist, who hopes to create and

perpetuate the “need” for information capital among consumers. In this case MOM is highly successful in that

she not only appeals to her baseline consumer (Professor Farnsworth), but is also

able to convince the displaced laborer (Bender) of the necessity of the very

object that took his job (using only the thinly veiled tool of brainwashing). If nothing else, “Obsoletely Fabulous”

illustrates capitalism’s primary and most deeply rooted interest: its own

self-preservation. Whatever the jobs in

information capitalism are, they will serve these interests above all others.

Works Cited

Carchedi, Guglielmo. “High-Tech Hype: Promises and Realities of Technology in the Twenty-

First Century.” Davis Davis

Technology, Information, Capitalism and Social Revolution. London

Technology, Information, Capitalism and Social Revolution. London